Understanding Letterboxing, Pillarboxing, and Cinema Aspect Ratios

A Simple Guide to Understanding Black Bars, Screen Shapes, and Video Formatting

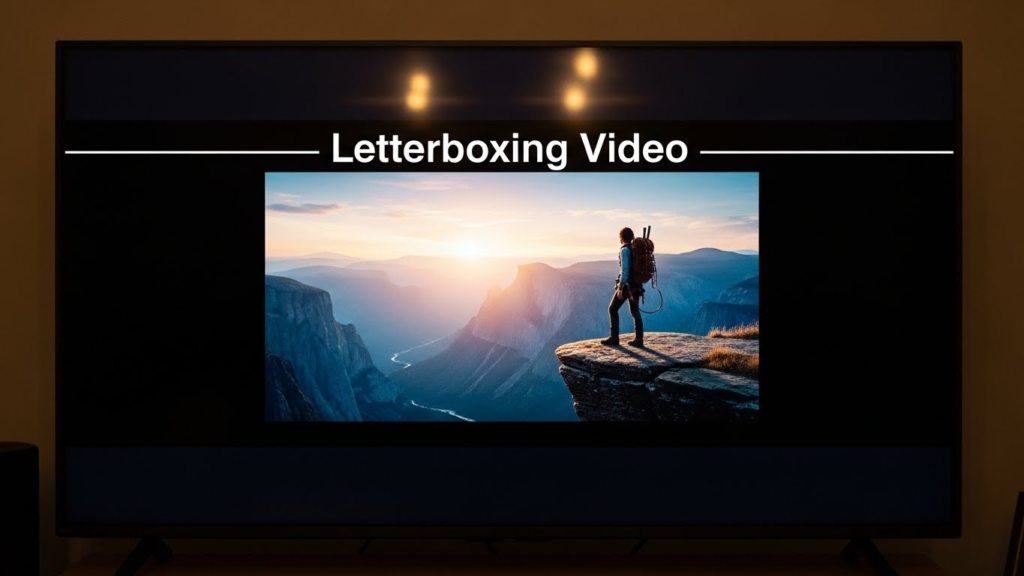

Watching a movie or video and suddenly seeing black bars on the top and bottom—or sometimes on the sides—is extremely common. Many people assume the video is low quality or poorly edited, but in reality, these black bars have a purpose. They are a part of a formatting method known as letterboxing video, which helps preserve the original presentation of a film.

In this easy article, we’ll break down letterboxing, pillarboxing, and the different cinema aspect ratios that shape what you see on your screen. No technical background needed—just simple explanations.

What Is Letterboxing Video?

Letterboxing refers to placing black bars above and below a video so it can fit properly on a narrower screen without cropping the original frame.

This method is used to preserve the director’s intended composition, especially for widescreen films.

Letterboxing video became popular when television screens had a 4:3 aspect ratio, but even with today’s 16:9 displays, ultra-wide movies still require letterboxing to fit correctly.

Why? Because the screen shape does not match the original film’s aspect ratio.

Why Black Bars Appear on Your Screen

Black bars appear for one reason:

Your screen’s aspect ratio doesn’t match the video’s aspect ratio.

For example:

- Your TV or phone screen is usually 16:9 (1.78:1)

- Many films are shot in 2.35:1 or 2.39:1 (CinemaScope)

The wider the movie, the more the device needs to compensate by adding black bars. Without letterboxing video, the film’s sides would be cut off, ruining the visual story.

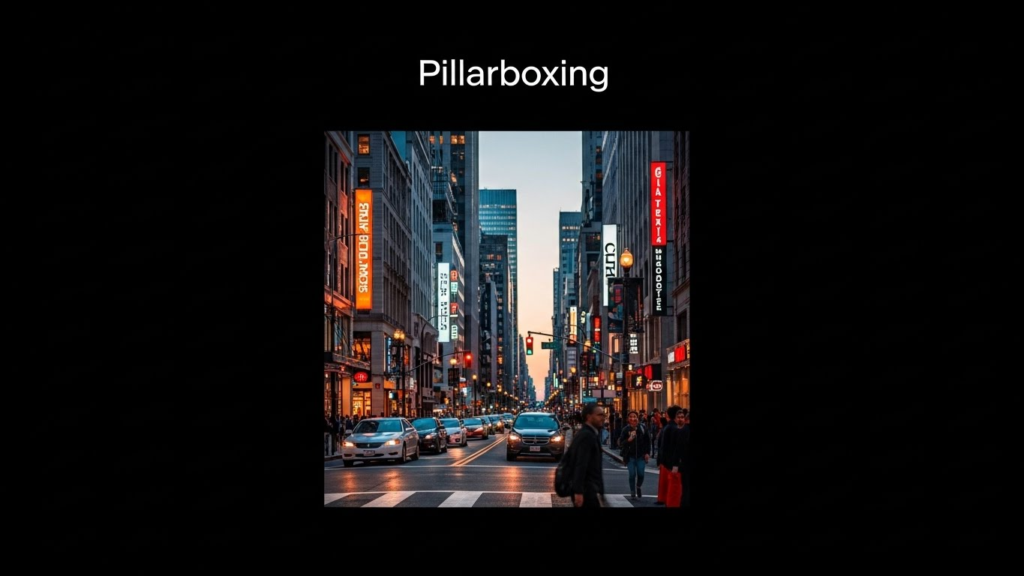

What Is Pillarboxing?

While letterboxing adds bars at the top and bottom, pillarboxing adds bars on the left and right of the video.

This occurs when a narrow video is shown on a wide screen.

Examples:

- Old TV shows shot in 4:3 displayed on a 16:9 TV

- Vertical or square videos displayed on horizontal screens

- Classic films that were never remastered for modern displays

Pillarboxing protects the original quality instead of stretching the image unnaturally.

Common Cinema Aspect Ratios Explained

Aspect ratio means the width-to-height proportion of a screen or video.

Here are the most commonly used ones:

1. 4:3 (1.33:1)

- Old TVs and classic broadcasts

- Square-like appearance

- Often pillarboxed on modern screens

2. 16:9 (1.78:1)

- Standard for TVs, smartphones, YouTube

- Most common modern display format

3. 1.85:1 (Standard Widescreen Film)

- Used in many Hollywood films

- Slight letterboxing on some screens

4. 2.35:1 / 2.39:1 (CinemaScope)

- Very wide cinematic format

- Requires letterboxing video on nearly all consumer screens

- Creates a more dramatic, immersive feel

Why Filmmakers Choose Wider Aspect Ratios

Filmmakers don’t use wide formats just for style—they are storytelling tools.

Wider ratios allow:

- More landscape in frame

- Better visual drama

- Smooth panoramic movement

- Epic cinematic composition

Movies like Interstellar, Dune, and Avatar use large aspect ratios to give audiences a big-screen experience—even at home.

How Devices Handle Letterboxing Video

Each device adapts differently:

Televisions

- Add black bars automatically

- Keep colors and resolution intact

- Avoid stretching which causes distortion

Mobile Phones

- Often let users zoom-in

- Zoom removes black bars but crops the video

- Letterboxing protects the full scene

Laptops and Monitors

- Behave similarly to TVs

- Some allow custom screen fit modes

Letterboxing video ensures the scene stays complete regardless of the device.

Does Letterboxing Reduce Quality?

No.

Letterboxing does not reduce video quality—it simply displays the original frame with empty space.

The visible image maintains:

- Original sharpness

- Correct proportions

- Authentic colors

- Intended framing

If a video looks blurry, it’s due to resolution (480p, 720p, 1080p), not letterboxing.

What Happens If You Remove Letterboxing?

Removing or correcting letterboxing video incorrectly can lead to:

❌ Cropped frames

Characters may be partially cut off.

❌ Stretched images

Faces look unnaturally wide.

❌ Loss of artistic intent

Directors frame scenes very carefully.

❌ Misaligned subtitles

Especially when subtitles are embedded in the black bar area.

So, letterboxing is not a defect—it’s protection.

Where Letterboxing Video Is Most Common

You will see letterboxing in:

- YouTube videos shot in ultra-wide formats

- TikTok cinema-style videos

- Netflix movies

- Hollywood theatrical releases

- DSLR or mirrorless camera video shoots

- Drone cinematic footage

Content creators intentionally use wide formats to give footage a cinema look.

Is Letterboxing Good or Bad?

It depends on what you want.

✔ Good if you want:

- Full cinematic experience

- Correct framing

- No distortion

- Professional look

✔ Not ideal if you want:

- Full screen coverage

- No black bars

- Zoomed visuals

But overall, letterboxing video is widely accepted because it preserves the purity of the original work.

Final Thoughts

Letterboxing and pillarboxing aren’t errors—they are formatting methods that ensure videos look correct on different screens. As long as filmmakers continue using widescreen formats, black bars will remain a natural part of the viewing experience.

Understanding these terms helps you appreciate video presentation and avoid the common confusion about “why black bars appear.”

If you’re a creator, choosing the right aspect ratio can completely transform your visuals. And if you’re a viewer, letterboxing video ensures you’re seeing the film exactly as it was meant to be seen.